CIVIL

WAR CANNON

CIVIL

WAR CANNON

The American Civil War has been called the last of the ancient wars and the first of the modern wars. It was a war which introduced the first metallic rifle and pistol cartridges, the first repeating rifles and carbines, the first ironclad ships, and many other inventions which herald a change in warfare. But the military still relied on the old tried and trusted means of smoothbore muskets, paper cartridges, and troops marching in military precision across the battlefield towards the enemy. More innovations and experimentation took place during the Civil War than during all other previous wars combined. This mix of technology was very evident in the ordnance department.

Prior to 1860, the United States government offered little encouragement to, and even less interest in, the inventions and experiments being offered by various ordnance experts. The general opinion of the U.S. Ordnance Department was that smoothbore cannons had won the previous wars and nothing further was needed. Many of the Ordnance Department employees were elder military officers who resisted any changes or departures from these smoothbore field guns, Napoleons, howitzers, and Columbiads. As a result, American inventors were subjected to years of expensive experimentation, field trials, and political bickering just to be able to introduce their ideas to the government. Many of these inventors invested their own money into their projects and faced financial ruin if the government turned their invention down.

Meanwhile, in Great Britain inventors were encouraged by their government to implement the rifling system in both small arms and artillery. Rifling was a system of lands and grooves in a barrel which caused a projectile to turn as it exited the muzzle, thereby improving trajectory and accuracy. The grooves were cut into the smoothbore gun and the lands were the original diameter and spaces left after the rifling process. Rifled weapons had to be stronger than smoothbore because a greater stress was inflicted on the gun by a tighter seal (less windage) necessary for the projectile to take the rifling, resulting in vastly greater pressures in the breech to overcome the friction between the projectile and the rifled bore. The pre-war years saw many patents granted to British inventors. These weapons would render important service to the opposing armies in the Civil War.

During this pre-war period, Englishman Bashley Britten patented the Britten projectile on August 1, 1855. Britten pioneered a method which cast a lead sabot onto the iron shell. Upon being fired the sabot expanded and took the rifling in the cannon barrel. Variations of this system were used on a multitude of projectiles during the Civil War. Britten continued to experiment with and patent rifled projectiles and lead sabots for several years.

The reluctance of the United States Government to entertain improvements

in artillery ended when, on April 12, 1861, at 4:30 A.M., Confederate Army

Lieutenant Henry S. Farley pulled the lanyard on his mortar at Fort

Johnson, South Carolina. The shell he fired arched high over Charleston

harbor and exploded above Fort

Sumter,

thus beginning the first sustained artillery duel of the Civil War.  Although

this was not the first hostile shot fired (the unarmed Federal supply ship, Star

Of The West, was fired on by Confederates in Charleston harbor on

January 9, 1861), it did, for all intent and purposes, signal the beginning

of four years of bloody conflict. The Blakely projectile was one of the

first rifled projectiles to be fired at Fort Sumter.

Although

this was not the first hostile shot fired (the unarmed Federal supply ship, Star

Of The West, was fired on by Confederates in Charleston harbor on

January 9, 1861), it did, for all intent and purposes, signal the beginning

of four years of bloody conflict. The Blakely projectile was one of the

first rifled projectiles to be fired at Fort Sumter.

Although the Confederates forced the surrender of Fort

Sumter, the new nation found itself woefully short of ordnance and other

military weaponry. Most of the artillery in the South came from the local

Federal forts and armories captured by the Confederates shortly after

hostilities commenced. This inventory consisted of quite a number of heavy

siege and seacoast artillery pieces but only a small number of field pieces.

The Confederacy also had a handful of antique and worn-out smoothbores which

had been relegated to local militia and home guards years before.

the new nation found itself woefully short of ordnance and other

military weaponry. Most of the artillery in the South came from the local

Federal forts and armories captured by the Confederates shortly after

hostilities commenced. This inventory consisted of quite a number of heavy

siege and seacoast artillery pieces but only a small number of field pieces.

The Confederacy also had a handful of antique and worn-out smoothbores which

had been relegated to local militia and home guards years before.

Since the South had only one working cannon foundry at the beginning of hostilities (Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia), it was imperative to quickly start the political and business maneuvering essential to establishing import trade from Europe. Over the next four years, Great Britain would prove to be the most productive exporter to the South. But, business being business, the British were not hesitant to trade with the Federal government, although on a restrictive basis.

The Federal forces began the war with over 4,000 pieces of artillery, but field artillery accounted for less than 165 of these weapons. With the distinct advantage of having several foundries able to shift over to wartime production, the North could rely on the raw materials to produce a formidable artillery arm and augment it with a few imports and captured Southern weapons. This was an advantage the South was never able to overcome and, with the tightening of the Federal blockade of Southern ports, the Confederacy had to rely more on the fortunes of battle to capture Union artillery and ammunition. By the end of the war, the South still had only a handful of armories and foundries compared to those in the North.

While the focus of this work is on projectiles, a brief discussion of the different artillery weapon systems is appropriate at this time. The reader should keep in mind that this is introductory material and many variations and types of artillery weapons exist which are not presented here.

Cannons can be divided into several categories according to their basic design, weight (heavy or light), barrel length, maximum effective elevation and range, and type of projectiles employed. For ease of identification and discussion, weapons will be grouped under guns and howitzers, mortars, and Columbiads. Weapons identified by the inventor's name will be grouped separately.

In addition to these categories, most artillery can be further divided into the type service performed: field (light and easy to maneuver through difficult terrain); mountain (quickly broken down for transportation on horseback); siege and garrison (heavy, but could be transported to different positions on siege lines or mounted in fortifications); and seacoast (heavy, cumbersome weapons which were usually mounted in forts or other areas along river banks and coastal waterways).

The reader will also encounter size designations of weapons in two variations. Many weapons were classified by the weight of the projectile fired and were known by "pounder" (i.e. 10-pounder, 20-pounder, 30-pounder, etc.). This should not be confused with the weight of the cannon itself but refers to the weight of the solid shot projectile intended for that particular cannon. Other weapons were classified by the diameter of the bore of the tube (barrel) such as the 3-inch wrought-iron rifle known as the Wrought-iron rifle or Ordnance rifle. On occasion a weapon may be listed by both designations. See Caliber to Pounder Relationships for further clarification.

GUNS AND HOWITZERS

Guns and howitzers are the weapons most people think about when Civil War artillery is discussed. These weapons were usually formed in batteries - that is, a group of six weapons (at least in the Union Army). At the beginning of the war, a battery contained four guns and two howitzers. A 6-pounder battery usually contained four 6-pounder guns and two 12-pounder howitzers, and a 12-pounder battery would be made up of four 12-pounders and two 24-pounder howitzers. Four-gun batteries were also common, especially in the Confederate Army.

Several batteries were often placed together in line to form a deadly defensive position. As the enemy troops advanced towards these batteries the guns would belch forth case shot (shells with lead or iron balls inside) and shrapnel shells. The prospect of being wounded or killed caused many soldiers to run or try to find a hiding place. Many veteran troops would throw themselves to the ground just as the weapons to their front fired. Once the weapons had been discharged, these troops would rise up and rush towards the guns hoping to capture the crew before they could reload. Since most proficient crews could fire two rounds per minute, the troops could find themselves hugging the ground several times.

Guns and howitzers differed in several aspects. A gun was a

long-barreled, heavy weapon which fired solid shot at long range with a low

degree of elevation using a large powder charge. A howitzer

had a shorter

barrel and could throw shots or shells at a shorter range but at higher

elevation with smaller powder charges. Howitzers

were lighter, more maneuverable weapons than guns.

had a shorter

barrel and could throw shots or shells at a shorter range but at higher

elevation with smaller powder charges. Howitzers

were lighter, more maneuverable weapons than guns.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, most artillery guns were smoothbore. Soon after hostilities opened the two forces began the task of re-boring and rifling the old smoothbores in order to accommodate the new ammunition being developed.

Guns and howitzers were usually designated by the year in which a particular model was designed or improved. Thus, a particular weight weapon may have many different model designations.

The Federals produced bronze 6-, 9- (fewer than thirty 9-pounders were produced), and 12-pounders for field use; iron 12-, 18-, and 24-pounders for siege and garrison use; iron 32- and 42-pounders for seacoast defense; and iron 32-, 42-, and 64-pounders for navy use. The Confederates produced iron 6-pounders and bronze (later iron when bronze became scarce) 12-pounders, both for field use.

The most popular and dependable gun was the Model

1857, commonly called Napoleon (named after the French emperor Louis

Napoleon who supported development of the design). This 12-pounder

smoothbore was effective, reliable, and easily maneuvered. It had a

range of 1,600 yards at five-degrees elevation and for best effect was

probably around 1,200 yards. The Confederate army used many captured

Napoleons as well as developing their own copy. When bronze became

scarce in the South, the guns were cast of iron. Although the Napoleon is

listed here as a gun, it was also classified as a gun-howitzer because of

its shorter barrel and light weight.

Other guns considered as standard, or common, weapons for the Civil War were the Model 1841 6-pounder field gun; Model 1841 32-pounder seacoast weapon; and the Model 1841 42-pounder seacoast gun.

Howitzers were originally developed in the near the turn of the 18th century. Most howitzers were smoothbore weapons, although many were rifled during the war as in the 3.4-inch Dahlgren Boat Howitzer. Howitzers produced by the Federals included bronze 12-, 24-, and 32-pounders for field use, iron 24-pounders and 8-inch for siege and garrison, and iron 8- and 10-inch for seacoast defense. The Confederates also produced iron 12-pounder and bronze 24-pounder field guns, and an iron 8-inch siege and garrison weapon.

The Model 1841 12-pounder was the standard field howitzer used in the Civil War. Because of its higher trajectory at which it was typically fired, it could fire a shell over 1,000 yards with less than one pound of powder.

"WHISTLING DICK"

One of the most famous gun of the war was "Whistling Dick", a banded and rifled 18-pounder Confederate siege and garrison weapon. "Whistling Dick" began life as a iron smoothbore Model 1839 which had been rifled. Because of some erratic rifling all shells fired from the gun made a peculiar whistling sound, thus the name "Whistling Dick." The gun was part of the river defenses at Vicksburg, Mississippi in 1863, and is credited with the sinking of the Union gunboat Cincinnati. "Whistling Dick" disappeared after the surrender of Vicksburg and remains unaccounted for today.

MORTARS

Mortars were stubby weapons which fired heavy projectiles in a high arc. Only a small powder charge was needed to project the shot or shell to its maximum elevation.

When a mortar shell exploded, fragments weighing as much as ten or twenty

pounds could fall with extreme velocity on the enemy. Combatants and

non-combatants alike, became adapt at constructing bomb-proofs to protect

themselves from fragments and solid shot. Bomb-proofs were shelters

dug

into the side of a bank, away from the enemy, or constructed inside

breastworks as small huts with heavy

layers of dirt on the top side. The morale of a besieged city or of troops

waiting to go into battle was severely affected by a mortar attack.

dug

into the side of a bank, away from the enemy, or constructed inside

breastworks as small huts with heavy

layers of dirt on the top side. The morale of a besieged city or of troops

waiting to go into battle was severely affected by a mortar attack.

At night, the lighted fuzes of the shells were easily observed and the

path of the shell could be traced during flight. During the day, the muzzle

fire of a was difficult to detect since the weapons were masked from

view of the opposing forces by the topography (ravines, woods, hills, etc.)

of the battlefield.  Mortars were most beneficial when the target was above

or below the level line of sight. These conditions caused elevation problems

for the long barreled weapons but allowed the short mortars to operate with

efficiency. Elevation adjustments were accomplished by means of a ratchet

and lever mechanism. Occasionally mortars were mounted on the decks of

ships, on special barges, or on railroad

flatcars.

Mortars were most beneficial when the target was above

or below the level line of sight. These conditions caused elevation problems

for the long barreled weapons but allowed the short mortars to operate with

efficiency. Elevation adjustments were accomplished by means of a ratchet

and lever mechanism. Occasionally mortars were mounted on the decks of

ships, on special barges, or on railroad

flatcars.

Most mortar projectiles can be recognized by tong holes, or tong ears, which are cast into the metal on either side of the fuze hole. This allowed the ball to be centered properly in the short tube.

Seacoast mortars were designated as 10- and 13-inch and were made of iron. Also known as heavy mortars, these weapons were primarily used for the defense of the rivers and coastal waterways. These mortars had a lug cast over the center of gravity to aid in mounting the heavy weapon.

Siege and garrison mortars were constructed to be light enough to be transported by an army on the march. They were also used in the trenches at sieges and in defense of fortifications. These 8- and 10-inch weapons were made of iron.

The familiar bronze Coehorn mortar was classified as a siege and garrison weapon. Named after its Dutch inventor, Baron Menno van Coehoorn (1641-1701), it was usually designated as 5.8-inch, but was also commonly referred to as a 24-pounder. The Coehorn was light enough to be carried by two men along the trench lines. The Confederates also produced a 12- and 24-pounder size made of iron.

THE "DICTATOR"

Perhaps the most

famous mortar used during the war was the "Dictator." This weapon was a 13-inch Model 1861 seacoast mortar which was mounted on a

specially reinforced railroad car to accommodate its weight of 17,000

pounds. Company G of the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, served the

"Dictator" at the siege of Petersburg,

Virginia in 1864. The mortar could lob a 200-pound

explosive shell about 2 ½ miles. The "Dictator" was usually positioned

in a curved section of the Petersburg & City Point Railroad and was

employed for about three months during the siege.

This weapon was a 13-inch Model 1861 seacoast mortar which was mounted on a

specially reinforced railroad car to accommodate its weight of 17,000

pounds. Company G of the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, served the

"Dictator" at the siege of Petersburg,

Virginia in 1864. The mortar could lob a 200-pound

explosive shell about 2 ½ miles. The "Dictator" was usually positioned

in a curved section of the Petersburg & City Point Railroad and was

employed for about three months during the siege.

COLUMBIADS

A Columbiad was a heavy iron artillery piece which could fire shot and shell at a high angle of elevation using a heavy powder charge. Columbiads were usually classified as seacoast defense weapons and were mounted in fortifications along the rivers and other waterways.

The original Columbiad, a 50-pounder, was invented in 1811 by Col. George Bomford and it was used in the War of 1812. Shortly afterwards it was considered obsolete and retired.

The weapon was produced again in 1844 in 8- and 10-inch models. In 1858, a version was produced which eliminated the chamber in the breech, which strengthened the gun. In 1861, Lt. Thomas J. Rodman, of the U.S. Ordnance Department, contracted with the Fort Pitt Foundry in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to produce Columbiads using a special casting method he had developed in 1844. His process, which caused less stress on the gun during casting thereby preventing cracks from forming, was a success and the Columbiad became widely known as a Rodman gun.

Columbiads were produced in 8-, 10-, 12-, 13-, 15-, and 20-inch models and were primarily smoothbore even though a few rifled models were turned out. The Confederates continued to produce their Columbiads by the old method and experimented with banding and rifling the weapon. Under this method, a Confederate Columbiad was capable of firing a 225-pound shot a distance of 1,800 yards.

Compared to guns, howitzers, and mortars, the Columbiads saw very little action. By the end of the Civil War these heavy weapons were obsolete, replaced by more effective weapons which had been developed during the war.

OTHER CANNON

As has been stated earlier, the pre-Civil War era saw a great deal of experimentation and innovation both in the United States and in Great Britain. With the interest of the government renewed in obtaining the best possible weapons, many inventors were able to step forward and convince the ordnance department to give their weapons a fair trial. The Confederacy also shared this sense of immediacy.

The following weapons are those which were produced or used in large quantities during the conflict. Many other weapons were also developed but were produced in small numbers or were not commonly used and, therefore, are not included here.

PARROTT CANNON

One famous U.S.

inventor was a former West Point graduate and ordnance officer named Robert

Parker Parrott.

In 1836, Parrott resigned his rank of captain and went

to work for the West

Point Foundry at Cold Spring, New York. This foundry was a civilian

operated business and Parrott, as a superintendent, was able to dedicate

some forty years perfecting a rifled cannon and a companion projectile. By

1860, he had patented a new method of attaching the reinforcing band on the

breech of a gun tube. Although he was not the first to attach a band to a

tube, he was the first to use a method of rotating the tube while slipping

the band on hot. This rotation, while cooling, caused the band to attach

itself in place uniformly rather than in one or two places as was the common

method, which allowed the band to sag in place. The 10-pounder

Parrott was patented in 1861 and the 20-

and 30-pounder guns followed in 1861. He quickly followed up these patents

by producing 6.4-, 8-, and 10-inch caliber cannons early in the war. The

Army referred to these as 100, 200,

and 300-pounder Parrotts respectively. By the end of the conflict the

Parrott gun was being used extensively in both armies.

In 1836, Parrott resigned his rank of captain and went

to work for the West

Point Foundry at Cold Spring, New York. This foundry was a civilian

operated business and Parrott, as a superintendent, was able to dedicate

some forty years perfecting a rifled cannon and a companion projectile. By

1860, he had patented a new method of attaching the reinforcing band on the

breech of a gun tube. Although he was not the first to attach a band to a

tube, he was the first to use a method of rotating the tube while slipping

the band on hot. This rotation, while cooling, caused the band to attach

itself in place uniformly rather than in one or two places as was the common

method, which allowed the band to sag in place. The 10-pounder

Parrott was patented in 1861 and the 20-

and 30-pounder guns followed in 1861. He quickly followed up these patents

by producing 6.4-, 8-, and 10-inch caliber cannons early in the war. The

Army referred to these as 100, 200,

and 300-pounder Parrotts respectively. By the end of the conflict the

Parrott gun was being used extensively in both armies.

Parrott's name is also associated with the ammunition fired by his cannon. The elongated Parrott projectile employed a sabot made of wrought iron, brass, lead or copper that was attached to the shell base. When the projectile was fired, the sabot expanded into the rifling of the tube. In 1861 Parrott patented his first projectile with the sabot cast on the outside of the projectile. A controversy arose after the war between Dr. John B. Read, who had actually invented this expansion system, and Parrott, who contended he had brought the 1856 and 1857 patents from Read before the war. As a result, these shells are often referred to as Read-Parrotts.

THE "SWAMP ANGEL"

In preparation for the

bombardment  of

Charleston, South Carolina, in August, 1863, Major

General Quincy Gillmore ordered the construction of a battery

in the swampy marsh near Morris Island. An 8-inch, 200-pounder

Parrott siege gun was mounted, under fire from the Confederates, and

promptly began firing incendiary shells into the city. This gun, named the "Swamp

Angel" continued firing for two days until, on the thirty-sixth

round, the gun exploded. But, it had caused a tremendous amount of moral

damage in Charleston and went into history as the most famous Parrott gun.

of

Charleston, South Carolina, in August, 1863, Major

General Quincy Gillmore ordered the construction of a battery

in the swampy marsh near Morris Island. An 8-inch, 200-pounder

Parrott siege gun was mounted, under fire from the Confederates, and

promptly began firing incendiary shells into the city. This gun, named the "Swamp

Angel" continued firing for two days until, on the thirty-sixth

round, the gun exploded. But, it had caused a tremendous amount of moral

damage in Charleston and went into history as the most famous Parrott gun.

3-INCH WROUGHT IRON RIFLE

(ALSO CALLED THE ORDNANCE RIFLE)

The Model 1861 3-inch wrought iron rifle, sometimes called an Ordnance rifle, was also a common weapon. The original design was patented in 1855 and was not quite what we know as the ordnance rifle; there was an evolutionary process both in achieving the final smooth profile of the piece, and the wrought iron, wound and welded in criss-crossing spirals in the original patent, was apparently done in sheets or plates for the final form of the gun. The Ordnance Rifle was manufactured at the Phoenix Iron Company in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. It was adopted by the Federal Ordnance Department in early 1861. Other versions of this weapon were produced in 1862 and 1863 by different companies, but this is the only weapon officially known as the Ordnance gun. The Confederates also produced their own version of this gun.

This weapon could accurately fire Schenkl and Hotchkiss shells approximately 2,000 yards at five degrees elevation, using a one pound charge of powder. The Hotchkiss shell was the most common projectile fired from the Model 1861. It was designed by Benjamin and Andrew Hotchkiss as a three piece shell - nose (containing the powder chamber), sabot (soft lead band fitting into an intention in the middle of the shell), and an iron forcing cup at the base (which forced the lead sabot to expand upon firing).

The other shell for this rifle was the Schenkl. This was a cone shaped projectile which employed ribs along the taped base. The sabot was made of papier-mâché' which was driven up the taper by the force of the gas produced upon firing. The sabot then expanded and caught the rifling in the tube.

This gun is sometimes erroneously referred to as a "Rodman." The process used by Thomas Rodman in casting the Columbiads was not used in producing the wrought iron barrel of the Ordnance gun. As far as can be determined, Rodman had nothing to do with the design or production of this gun.

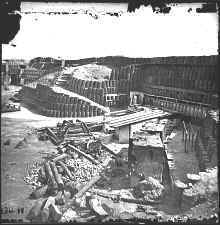

BLAKELY RIFLE

A British army

officer, Captain Theophilus Alexander

Blakely, pioneered a banding system for his rifled cannon. With each

experiment of his design a different cannon was developed with the end

result of at least five, and possibly as many as ten, distinct types of

Blakely cannons were manufactured.  Blakely cannon are photographed in

the foreground of this image of the Charleston

Arsenal.

Blakely cannon are photographed in

the foreground of this image of the Charleston

Arsenal.

The 3.5-inch caliber, 12-pounder Blakely weapons were developed in nine varieties, with a tenth variation being a 10-pounder mountain piece. Most of these weapons were iron. Blakely rifles were also manufactured in 3.75-, 4.5- and 6.3-inch, and 100-, 120-, 150-, 200-, 250-, 375-, and 650-pounder sizes. Most were of iron, with the exception of the 375-pounder, which was made of semi-steel.

One famous Blakely rifle was "The Widow Blakely" that was used by the Confederates during the defenses of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1863.

WHITWORTH

In Manchester,

England, in the late 1850's, Sir Joseph Whitworth patented a system

for

cannons (and small arms) which used a hexagonal bore design instead of the

usual rifling methods. The ammunition

also carried the hexagonal design in order to follow the bore, thus allowing

for better range and accuracy. Sir Whitworth manufactured his cannons in

both breech-loading and muzzle-loading

models. If the Whitworth breech-loader malfunctioned, it could very simply

be used a muzzle-loader on the battlefield.

for

cannons (and small arms) which used a hexagonal bore design instead of the

usual rifling methods. The ammunition

also carried the hexagonal design in order to follow the bore, thus allowing

for better range and accuracy. Sir Whitworth manufactured his cannons in

both breech-loading and muzzle-loading

models. If the Whitworth breech-loader malfunctioned, it could very simply

be used a muzzle-loader on the battlefield.

BROOKE GUN

Early in the war, John M. Brooke, late of the U.S. Navy and now an ordnance officer in the Confederate Navy, designed a banded cannon which was similar in appearance to the Parrott, but was different in the number of bands wrapped around the breech. The Brooke band consisted of several rings which were not welded together. Its rifling was similar to the Blakely gun and came in a number of calibers, including 6.4-inch, 7-inch, 8-inch, and 11-inch. John Brooke's other claim to fame was the key role he played in designing the armor plating used by the CSS Virginia (Merrimac) in the famous battle with the USS Monitor.

DAHLGREN GUN

Dahlgren weapons are

usually divided into three groups - bronze boat howitzers and rifles, iron

smoothbores, and iron rifles. The designer, John A. B. Dahlgren

of the U.S. Navy, developed the weapons primarily for use

on small boats that patrolled the waterways. The necessity for these weapons

was demonstrated by the Navy's experience during the Mexican War when small

launches and other craft were assigned to patrol close to river and creek

banks.

of the U.S. Navy, developed the weapons primarily for use

on small boats that patrolled the waterways. The necessity for these weapons

was demonstrated by the Navy's experience during the Mexican War when small

launches and other craft were assigned to patrol close to river and creek

banks.

Dahlgren was a Lieutenant when he was assigned to the ordnance department at the U.S. Navy Yard. The first weapon systems were adopted by the Navy in 1850. These bronze 12- and 24-pounder pieces were specially designed for use on the small launches, but were also included on most naval vessels during the Civil War. His iron smoothbores were adopted in 1850 (9-inch gun) and 1851 (11-inch gun). Although these guns were designed for use against wooden ships, the iron-clad Monitor class ships carried two of these in their turrets. These weapons were later replaced by the 15-inch Dahlgrens in 1862.

By the end of the Civil War, John Dahlgren, now a Rear Admiral, was responsible for the development and design of 12-pounder boat howitzers in several weight classifications (small, medium, and light), 20- and 24-pounder howitzers (some, including the 12-pounders, were rifled); 30-, 32-, 50-, 80-, and 150-pounder rifles; and 8-, 9-, 10-, 11-, 13-, 15-, and 20-inch rifles.

CONCLUSION

The importance of the artillery service cannot be overstated. Because artillery fire was apt to produce mass casualties when fired into an advancing line of enemy, it could also be used as a psychological weapon. A soldier advancing against artillery was often unnerved by the prospects of encountering canister, case shot, and shrapnel. Shot and shell fired into fortifications, besieged cities, or the reserve areas behind the battle lines could be quite uncomfortable for soldiers and civilians alike. Many first-person accounts of battles speak of the screams of the Parrott, James, and Hotchkiss shells produced by damaged or hanging sabots. The Whitworth projectile, by its very design, made an eerie whining sound during flight.

Besieged writers often commented on the unusual sound of the large projectiles fired by siege weapons. During the sieges of Vicksburg, Atlanta, and Richmond, the terms "wash kettles" and "wood stoves" were used quite often in describing the flight and impact of these heavy projectiles.

New tactics using artillery weapons were developed during the American Civil War which herald the beginning of modern warfare. "Flying batteries", first used by Confederate Artillery Major John Pelham, were effective in deluding the enemy into believing a greater artillery force opposed them than was actually present. Using a four gun battery, Pelham had his crews unlimber, fire, limber back up and quickly move to a new position to repeat the tactic. This tactic was particularly effective when the terrain could be used to mask this movement. Pelham's "flying batteries" tactics would be refined and used effectively in future wars as the military became more mobile.

A new era dawned on April 10 - 11, 1862,

when Federal Captain

Quincy A. Gillmore forced the surrender of Fort

Pulaski off the coast of Savannah, Georgia. Gillmore used land-based

mortars, smoothbores and, most importantly, rifled guns to breach a wall in

the masonry fort within thirty hours of commencing fire. Because of the

possibility of shells reaching the main powder magazine, the Confederate commander,

when Federal Captain

Quincy A. Gillmore forced the surrender of Fort

Pulaski off the coast of Savannah, Georgia. Gillmore used land-based

mortars, smoothbores and, most importantly, rifled guns to breach a wall in

the masonry fort within thirty hours of commencing fire. Because of the

possibility of shells reaching the main powder magazine, the Confederate commander,

Colonel Charles Olmstead, was forced to lower his flag. Gillmore repeated

this tactic in Charleston, South Carolina, in July, 1863, when he reduced

Fort Sumter to a pile of rubble. This tactic spelled the end for masonry

forts designed to withstand smoothbore bombardments of the ancient wars.

Colonel Charles Olmstead, was forced to lower his flag. Gillmore repeated

this tactic in Charleston, South Carolina, in July, 1863, when he reduced

Fort Sumter to a pile of rubble. This tactic spelled the end for masonry

forts designed to withstand smoothbore bombardments of the ancient wars.

The Civil War era inventors and their inventions changed the face of war forever. The improvements and innovations in the artillery field were mirrored in the changes that took place in the infantry, cavalry, medical, and naval departments. Many of the same basic principles developed or theorized during the Civil War are still present in modern warfare. Thus, the Civil War can live up to its billing as "the last of the ancient wars and the first of the modern wars". See Caliber to Pounder relationships for additional reading.

Read this informative article on Technology and the Development of Field Artillery through the American Civil War, 1861-65